Over the last few days I received notes from friends and colleagues expressing concern that ChatGPT will be the end of writing.

These are intelligent, caring people. I can’t imagine any of them ever outsourcing their expressions of thoughts and feelings to an AI Chat Bot. Each considered the issues and wrote to start a conversation with me. That’s the main reason I read their emails.

I want to reassure these fine folks, and you, dear reader, that ChatGPT will have about the same impact on writing as sex toys have on sex. It’s an interesting novelty and potentially a useful augmentation in some circumstances. It’s just not the same as the real thing.

Here are five reasons why:

- Writing supports connection.

- Imperf3ction is a brilliant teacher.

- The argument is not about the argument.

- School sucks.

- Communication skills grow from human needs.

- Utopian dystopia.

Reason 1. Writing supports connection.

As writers and readers we agree on shared meanings for basic units of currency, like the letters I’m using to construct the words in this sentence.

This agreement about language and meaning brings us together. It allows us to share the rest of our humanity through a medium that, when you think deeply about it, is nothing sort of magical. We write to understand and be understood.

The defining qualities of humanity are interdependence, a shared sense of imperfection, and the unifying power of story. These ideas are all write* (*right) their* (*there) in the very first words of our Constitution, the story we learn, and try to live by, and teach our children about our nation: “We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union…”

Take another look at the imperfections in that last paragraph. Not just the homonyms I included as dorky examples of human error, but at the capitalization in the text of the Constitution. The framers made a style choice to capitalize order and union for emphasis. No self-respecting (that’s a sentience joke, I’ll get to that topic later) AI software would do this, because there is no grammatical rule in the English language that supports or validates the practice. In fact, any English teacher would be well within their rights to ding a student for capitalizing common, abstract, uncountable nouns in the middle of a sentence.

However: that first line of the Constitution sets the tone for one of the most important, most highly regarded documents that human beings have ever produced. Apart from the howling freaks on the far right who make even less sense than English grammar rules, who would dare step up and mark down the Constitution?

rEason 2. Imp3rfection Is a Brilliant Teacher

I taught undergraduate and graduate communication studies, education, and management courses at UCLA for eleven years. Then I taught high school English for fifteen years. I taught nearly every English course in the California state curriculum for grades 9-12, from ELL to AP. My students wrote thousands of assignments, essays, blog posts, research papers, and related projects.

They were never perfect. Frequently students would write writting instead of writing, or use the wrong there, they’re, or their.

Each imperfection in a text is valuable information that offers insight. Some errors are manifestations of recognizable cognitive deficits, cultural misunderstandings of idioms, or gaps in secondary language acquisition. Every letter and punctuation mark reveals the author and provides a useful tool for evaluation, reflection, practice, and improvement.

Still, teaching writing does sometimes make you think twice about whether or not students should really use their own words.

Spoiler: They absolutely should, for the same reasons I occasionally invent a word, or split an infinitive, or start a sentence with and or but, or end with a preposition. Or throw in a dependent clause. But mostly because using our own words is a conversation starter that invites inquiry. If you see a mistake in this piece, or something you find curious, get curious and ask me about it. I found that conversation was the best way to expand and improve readers’ and authors’ thinking. Plus, the evaluative benefits of conversation obviate the concerns about AI. If I’ve spoken with a student even just a couple times, I can immediately tell when they are writing in their authentic voice. I can also tell when they are trying out unfamiliar words, and when they are plagiarizing.

(Sidebar: Imperfection is beautifully human, especially in the way it contributes to the suspense, tension, and even conflict that make stories worth following. Sports would be so dull without the potential tragedy of human error costing your team the big game.)

Writers of all ages teach us through their imperfections — and sometimes their perfect execution of imperfect intentions. Mark Twain’s use of the N word 200+ times in Huckleberry Finn is powerful evidence. But of what? That question is an opportunity to explore history, culture, economics, empathy, and so much more. A person’s writing — and occasionally writting — is a window into their understanding of ideas and the thought process through which they express themselves. You can learn a great deal about a person from their diction and syntax.

Besides, imperfections aren’t limited to textual examples. They include ethics and decision-making. You can also learn a lot about a person when they cheat, lie, or use an AI Chat Bot to produce an essay.

reAson 3. The Argument Is Not About the Argument

Let’s put this AI thing in historical context. We’ve been here before.

Oral historians didn’t like scrolls.

People who enjoyed scrolling (for real, a couple thousand years ago) didn’t like all that recto and verso funny business of the codex.

(“They said there would be no math!”) My seventh grade algebra teacher hated the calculator. She hated it even more when I did the assigned problems in my head without a calculator and STILL didn’t show my work.

Hunters and peckers don’t like the keyboard.

Fountain pen aficionados hate ballpoints.

Generations raised on encyclopedias don’t like Wikipedia.

The list goes on and on, and sometimes with good reason. A thing isn’t necessarily better just because it’s new or even more efficient and easier to use. For example, I type faster than I write. But the practice of handwriting develops memory, creativity, and capacity for mindfulness more effectively than tapping on a keyboard. You can probably identify some good reasons for all of the above arguments, if you’re inclined to look, just as you can find undigested berries in skunk poop. (I digress. More on stream of consciousness below.)

However, history teaches a valuable lesson about innovation. It’s not the thing itself that matters. Books didn’t ruin things for everyone who still wanted to remember stuff they were told or scroll through the written version. E-books didn’t ruin books. Calculators didn’t ruin math education, at least not all by themselves.

What we are really talking about here is the value of reading and writing in our culture, and the fact that many people feel that academic writing assignments are a steaming pile of time-consuming nonsense.

They are not entirely wrong.

reaSon 4. School Sucks

School requires adherence to state-approved curriculum that hasn’t changed much since the 19th century, when it was adopted to get white males into Harvard so they could enter the professions. I doubt that memorizing the quadratic formula and dissecting frogs on Taylor-esque Carnegie Unit schedules helped everyone back then, and I am certain that it doesn’t now.

One problem with school today is that students’ futures are not predictable. We have no idea what elementary school students will do for a living when they graduate high school or college, or what the economy — or the geopolitical landscape, or even our physical environment — will be like just a few years from now.

We should be curious about everything, including emerging technology like ChatGPT that invites us to question the roots of our practices.

However, with rare and wonderful exceptions, the institutional culture of school is not curious. It is hidebound and defensive. Be on the watch for people who use that classist, racist, and ugly phrase “academic rigor.” It’s a tell for dangerous self-preservationists who would destroy your child before admitting that the system that validated their existence never made any meritocratic sense in the first place.

School takes the most interesting parts of life and makes them so excruciatingly boring that children run as far as they can from learning and critical thinking. How else can we explain voting behavior, the popularity of fast food, or the fact that January 6 happened at all?

There is nothing so useless as doing efficiently that which should not be done at all.

Peter Drucker

Audrey Watters and others have chronicled school’s deranged use of technology in ways that do many wrong things more efficiently. Educators have misused everything from Alfred Binet’s test to laptop cameras. We should remember that this is a people problem, not a tool problem. As I pointed out in a TED talk I gave what feels like 738 years ago, a scalpel in the hand of a doctor can save a life, and the same sharp piece of metal in the hand of a criminal can take a life.

This is about context. People have created conditions in which some tools and practices (ChatGPT) are perceived as more attractive and useful than others (pencils and spiral notebooks).

School favors control. As journalist (read: writer) Glenn Greenwald put it, “Surveillance breeds conformity.”

The classroom is bad enough, but during the pandemic schools widely misused technology to spy on students at home. The results were predictably bad. Students with darker skin and students who don’t have the luxury of peace and quiet were punished by algorithmic bias.

Students wouldn’t feel a need to game the writing system in school if their teachers — in person or online — would simply get to know them well enough to recognize how they speak. Or engage them in conversation about their writing.

Demanding that young people write five-paragraph essays about ideas without much apparent value is a recipe for ensuring that no one wants to write. High school students experience essays as pain.

reasOn 5. Communication Skills Grow From Human Needs

AI doesn’t need anything. It is not sentient. It has no emotion, no sense of urgency.

We human beings do.

Writers write because they want something. They want to get an idea or a feeling out there where someone else can read it. They want their reader to … Know. Understand. Laugh. Get angry. DO SOMETHING!!!

Apart from our emotional needs to connect, we are practical, interdependent social animals. We need to share understanding in order to make transactions, collaborate, form social bonds, procreate, and do just about everything else in our daily lives.

The elements of interpersonal communication are the most important skills a person can develop. The more these elements must stand on their own, the more artful and specific they must be.

A written message doesn’t have the luxury of using facial expressions, tones of voice, or slamming the door as it leaves the room to create the effect its author intends.

Writing for understanding is difficult. When Montaigne coined the term “essay” to describe his attempts at capturing his thinking in writing, he commented that it was a “thorny undertaking, and more so than it seems, to follow a movement so wandering as that of our mind.”

Let’s honor that. These skills require more than meets the eye. Reading is more than sounding out words. Phonics are literally meaningless without understanding. I’ve watched students who pronounce words quickly and flawlessly completely blank out when I asked them a simple question about what they’d just read. They were classified “highly proficient” on the test but they couldn’t tell a takeout menu from a ransom note.

Writing is more than putting sentences together.

Writing is a time machine that connects our inner world of thoughts and feelings.

ReasoN 6. Utopian Dystopia

We human beings put ideas together in ways that don’t always appear to make sense. Take this section’s title for example: Utopian Dystopia. The two words contradict one another — when we perceive the conflict created by the contradiction, we experience stress and a desire to change or solve something to relieve the inconsistency. In the 1950s, social psychologist Leon Festinger called this phenomenon cognitive dissonance.

Our capacities for imagination and irony empower us to construct narratives that transcend our day to day reality. This is a distinguishing characteristic of our species. As Yuval Noah Harari writes in Sapiens, “Homo sapiens rules the world because it is the only animal that can believe in things that exist purely in its own imagination, such as gods, states, money, and human rights.”

There ain’t no AI that can create Lord of the Rings or Game of Thrones. Or use abruptly use the word ain’t without warning in an attempt to create a colloquial, conversation tone that puts an arm around the reader and says, “C’mon, man, this shit is ridiculous. Let’s get something to eat.”

As non-Chat Bot creator of worlds Isaac Asimov put it, “Today’s science fiction is tomorrow’s science fact.” William Gibson added, “The future is already here — it’s just not evenly distributed.”

So some of us have AI. And some of us still value the humanity of the written word and the way it brings us together with our deepest selves and each other.

The extent to which people adopt this tool — just like any tool — will be a function of their purpose and their understanding of the norms, attitudes, and values in the systems where they operate.

As for me, I don’t see the point in escalating the cleverness around writing. I believe in trust and integrity. Maybe that means someone occasionally fools me. But I maintain that online plagiarism detectors are for suckers. When I wasn’t sure about something I read, I asked my students questions about what they wrote.

Same with canned assignments. Busy work leads to bad product. Leave book reports in 1979 where they belong. When I read stories and novels with my students, and I wanted them to connect the text with their ideas about authors’ themes, tones, and techniques, I asked my students human questions. I wanted to know whether they thought an author got up early to do yoga or stayed out late drinking. Once they’d formed opinions, I asked them to support their ideas with textual clues from what they’d read.

The results were inimitably human. My students wrote on many topics that computers cannot understand or articulate with any real depth or emotion: broken hearts, family violence, drug addiction. Performative utterances. (When a computer talks itself into killing its uncle for sleeping with its mother, I reserve the right to reconsider everything I’ve written here.)

AI can do many things. ChatGPT is an impressive technology. But can it be whimsical? Delightful? Unexpected? Wrong? Ironic? Sarcastic?

Can it do this?

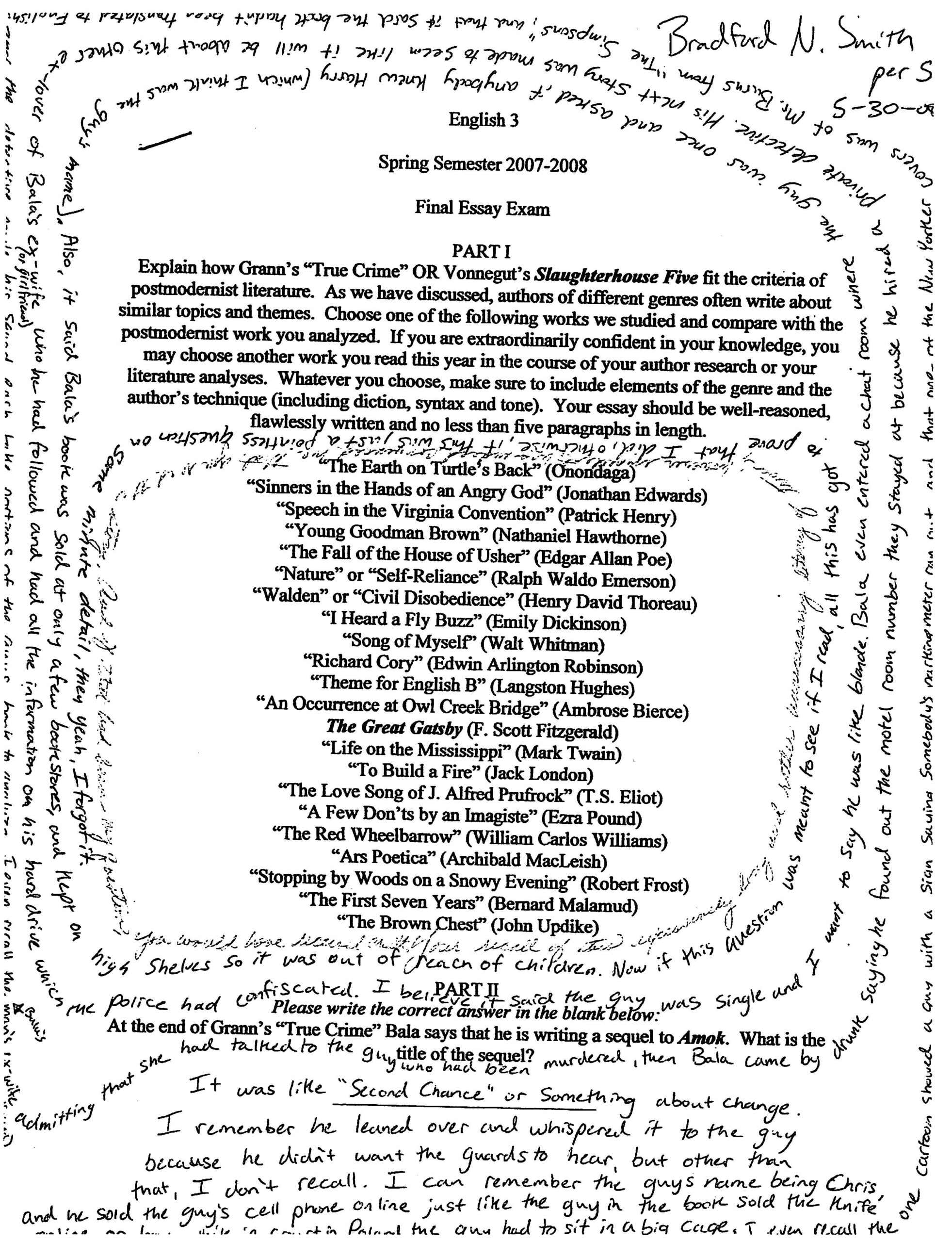

circular thinking essay bradford smith