Viktor Frankl

The meaning of life is to give life meaning.

Everything I do means something to me. At 3:45 on Sunday morning I pulled into the parking lot of the Indian Wells Tennis Gardens and did something I’d never done before.

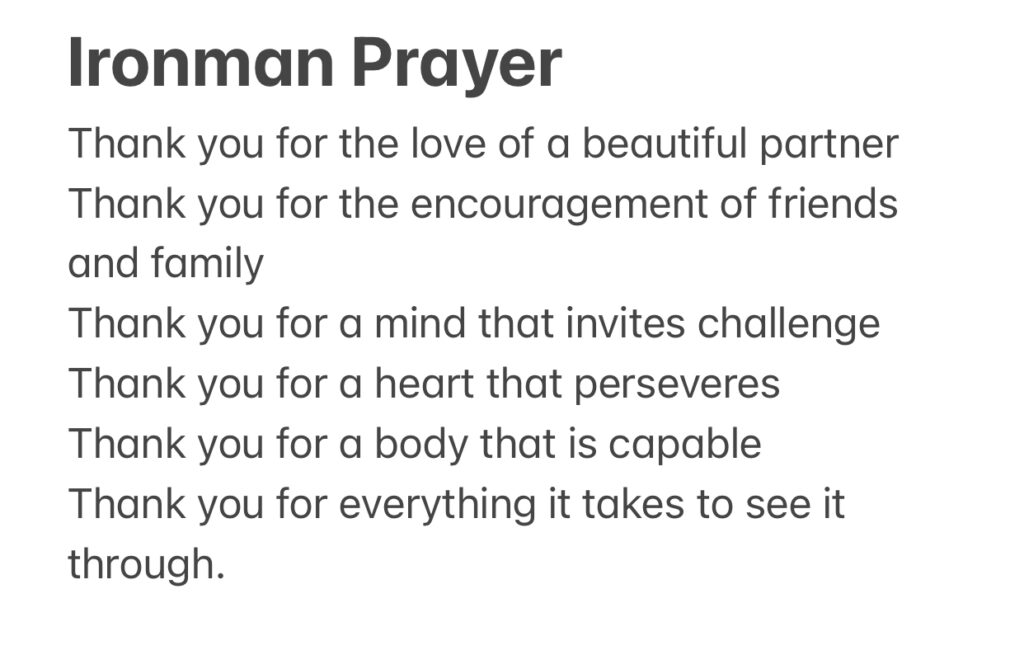

I wrote a prayer. I wasn’t asking for anything, I just had a strong, clear sense of gratitude and I wanted to remember it word for word.

None of us really does anything alone, but in today’s world it’s easy to feel alone. That’s why I included Civic Fitness (how we operate in the context of social systems) and Spiritual Fitness (how we operate in larger contexts that we can’t always observe or understand) in Open-Source Learning. Orienting ourselves in the big picture is a skill for which there is no GPS, no sign that says, “you are here.” Like any skill, being part of something bigger than yourself takes practice.

So, in that moment, I took a deep breath and quietly remembered everyone and everything that brought me to that moment in my life. I do this from time to time, especially when I’m about to embark on something big.

Here is what I wrote:

Then I turned off my phone, got out of the car, and spent the day completing my first Ironman triathlon. I swam 1.2 miles. I bicycled 56 miles. I ran 13.1 miles – half the distance of a marathon.

On the surface, my preparation for this event began in June, when I started my training calendar.

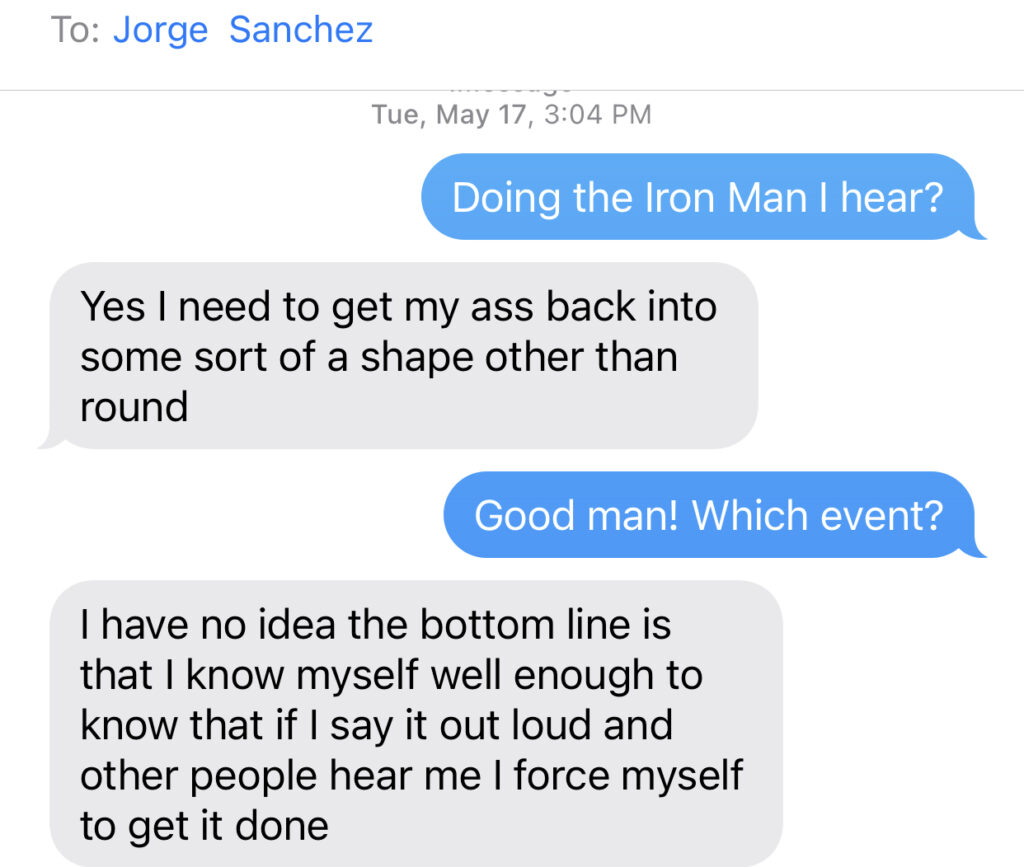

ironman-training-calendar-2022Or did it start back in May, when my neighbor started making noises about doing something bold to inspire himself to get into better shape?

The truth is, I’ve been training for this my whole life.

THE HAND I WAS DEALT

I was sick as a kid.

As an infant I had scarlet fever, asthma attacks, and allergies to everything from dust to pollen to a surprise, severe reaction to Penicillin. I was even allergic to citric acid. When my family got pizza for dinner I couldn’t eat the tomato sauce so they passed me the crusts. I learned early in life that tomorrow, and pepperoni, is promised to no one.

In elementary school, my best friend Preston (!) had a slumber party for his birthday four years in a row. But Preston also had a cat. I was so allergic that I couldn’t breathe in his house.

I went to the doctor every day after school for an allergy shot. Eventually I got to mow the lawn, but I am still allergic to cats, and I never did get to go to Preston’s parties. Four years in a row.

When I got asthma attacks at night my mom would shove me out the back door so the cold air would shock me into breathing. She did this out of love and it did the trick. When it didn’t we went to the ER for breathing treatments.

I had to sit in the front row of the school bus because less pollen blew in the front window.

During the smoggy 1970s in Los Angeles I spent school recess in the office, listening to my friends outside on the playground.

I’m not complaining. That’s just how it was.

But I was a kid, and when you’re a kid these things matter. I got frustrated. Eventually I got angry.

THE BET I MADE

People respond to life’s circumstances in different ways. I steer into the skid.

I responded to my physical limitations by doubling down. I pushed myself harder to participate in sports. Sometimes I succeeded, like when I made the soccer all-star team, led the baseball league in home runs, or became a lifeguard. Other times I failed or got hurt.

Back then I didn’t know about stoicism.

What stands in the way becomes the way.

–Marcus Aurelius

But the ups and downs definitely seemed related.

My mom, my teachers, and even some of my friends thought I was too intense, too serious, too hard-boiled. They weren’t necessarily wrong.

I broke my back on the soccer field when I was 12. My mom saw me limping and yelled at the coach to pull me out of the game because she saw that I wanted to keep playing. When we got to the hospital, the doctor told me that if I’d stayed in, and my vertebra had slipped another couple millimeters, I could’ve been paralyzed from the waist down.

I got off with a lesser sentence and had to wear a hard back brace for a couple months. I felt like a turtle. Kids teased me. That came to an end when I stepped to the school bully and dared him to punch me in the stomach, which he did, breaking his wrist.

Three years later I sent a letter to Cleveland High School basketball coach Bobby Braswell, who had “a reputation as being a tough coach,” telling him I intended to join his city-championship team.

What a sight I must have been. The scrawny white nerd running the stairs and lifting weights and suffering through conditioning with hood rats and future NCAA and NBA players. Those were the days before dehydration and concussions were a thing. We practiced for weeks without seeing a basketball. Sprints, drills, and stairs in the late summer San Fernando Valley heat. More sprints. If you threw up or passed out, you got cut. After a month of conditioning I was exhausted. My mom had to talk me into taking my uniform to school one last day before I quit. That was the day someone taped the roster to the trophy case just inside the gym entrance. My name was on it.

OVER THE YEARS

My great grandfather survived the Holocaust and got his daughters out of Germany. He loved paying taxes because: (a) he loved being American, and (b) it meant he had enough money to pay taxes. He said things like, “If you don’t have shoes, be glad you have feet.”

I wish my Opa could see how I took on challenges that made me stronger, how I drew inspiration from my ancestors and my mentors, and how I try to use everything in my own experience to help others.

My heroes have always been people who overcome adversity and obstacles. Ten days before my tenth birthday the Pittsburgh Steelers played the Los Angeles Rams in Super Bowl XIV. Everyone was amped up about the star players and the Steelers winning their fourth championship. I didn’t care about any of that. I watched the players who proved everyone wrong just by showing up: Pittsburgh’s Rocky Bleier, who made it back to football after getting blown up in Vietnam, and LA’s Jack Youngblood, who played the game with a broken leg.

I began to understand that my life is defined by the way I respond to it. My freshman year at UCLA I was bringing the ball up the Dykstra Hall court at full speed when I planted my foot to change directions. I caught my toe in the cracked asphalt, and my foot stayed straight while the rest of me turned 90 degrees to the right. I shattered all the bones and ligaments in my left knee. Everyone froze: the sound echoed off the dorm building like a rifle shot. I got up slowly and limped what was left of my ACL to the medical center. Two hours later I reported for my graveyard shift as a security guard in a full leg brace. A few weeks later I had the first of 11 knee surgeries.

In my twenties I was visiting my parents in Northridge when the earth quaked and the walls of my childhood bedroom collapsed on me. The epidurals and back surgery came later. The months of healing.

The week after I was cleared to get back to life, I was sitting in the back seat of my parents’ Oldsmobile on our way to celebrate with a rare dinner out. My Dad slowed for a red light. There was a loud crash, broken glass everywhere, and I was suddenly doubled over, my head folded into my lap by the heavy, hairy stench of alcohol. A drunk Harley rider had failed to stop, rear-ended us, and launched himself through the back windshield onto my shoulders. The police later reported that his Blood Alcohol Content was three times the legal limit. They estimated his speed was 45 mph on impact.

in my thirties I was surfing Old Man’s in San Clemente when an actual old man barged into my wave and sliced my head open with the fin of his board.

Whatever. The list goes on. Saving my then four-year-old daughter on a ski lift and tearing up my shoulder for the first of three rotator cuff repairs. Food poisoning. A lousy first marriage and a bunch of other crap that happens to everyone and isn’t worth mentioning.

TOMORROW IS PROMISED TO NO ONE

I am painfully aware that everyone has a list like this. Everyone – maybe even you too – has reasons to feel disappointed, or angry, or sad.

The thing is, the universe doesn’t care. It doesn’t owe us a thing. I’ve found a tremendous amount of freedom and power in realizing that I get out of this life exactly what I put in. Nothing more, nothing less. I wanted more. So I started putting in more.

People may know about Open-Source Learning, or Academy of One, but it’s the before and after hours stuff I’m talking about here.

20 years ago I signed up for the Arthitis Foundation’s weeklong bike ride from San Francisco to Los Angeles. Then I went out and bought a bike.

In 2004 and 2005 I ran the Los Angeles Marathon with sixth graders from Haddon Avenue Elementary in Pacoima.

In 2009 I ran the Big Sur Marathon just before my daughter was born, even though I was getting over pneumonia.

In 2020 I walked into Bobby Maximus’ gym.

TODAY I AM AN IRONMAN

I’m a month shy of 53 years old. I wear glasses and it’s been a long time since I could slam dunk a basketball.

When my neighbor first mentioned the Ironman, it seemed like a lofty, intimidating goal. I get what he was doing, trying to puff himself up like Hamlet getting up the nerve to kill his uncle. Big talk can pay off. That is why I took on the challenge and told people what I planned to do. I wanted to be accountable. I wanted to push myself to the next level.

And that’s exactly what I did over the next five months. I trained. Week in, week out. I did the work. My neighbor never showed up. It didn’t matter. I put in the miles. I did practice triathlons in Malibu and San Diego.

I met some truly amazing people along the way who I am now both proud and humbled to call my friends. I’ll introduce some of them here in future posts.

In the end, I did it. I earned the right to put my arm around that sick kid, that injured, surgically-repaired youth, that battle-scarred, caring man who worries about the world, and say with integrity: “You got this. You are an Ironman.”

Thanks for reading. Whatever you’ve got on your plate in life, I hope you pick something rewarding, something meaningful, and get after it. Put in the work. Suffer for it. It will pay you back. I promise.