How we engage with social media continues to increase influence our economy, our social and political culture, and our personal lives.

Open-Source Learning invites us to consider and reconsider how we engage with our devices, platforms, and software. Self-awareness has become more important than ever. An entire generation is growing up on the screen. Where is the parental guidance or any authoritative expertise that might mitigate the effects of addiction or gullibility. Whatever else you think is responsible for the Presidential election of 2016, the impact of social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter on our democracy is undeniable. Schools and organizations in the public and private sector have a responsibility to build awareness so that we can all make more informed decisions.

I originally wrote this post in 2016 for teachers who were learning about digital culture. More recently I shared it with high school juniors in an American Literature course. But if we’re going to restore and heal what has been damaged in our culture, you know who’s going to have to make different choices about technoculture?

All of us.

___________________________

WE EAT SOCIAL MEDIA FOR BREAKFAST

Over the years it has become popular for executives, management gurus, and pundits to quote the imaginary Peter Drucker line: “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.” (Or lunch, depending on the source.) The general idea is that our decisions and behavior are influenced by forces so subtle that we aren’t even aware of their existence.

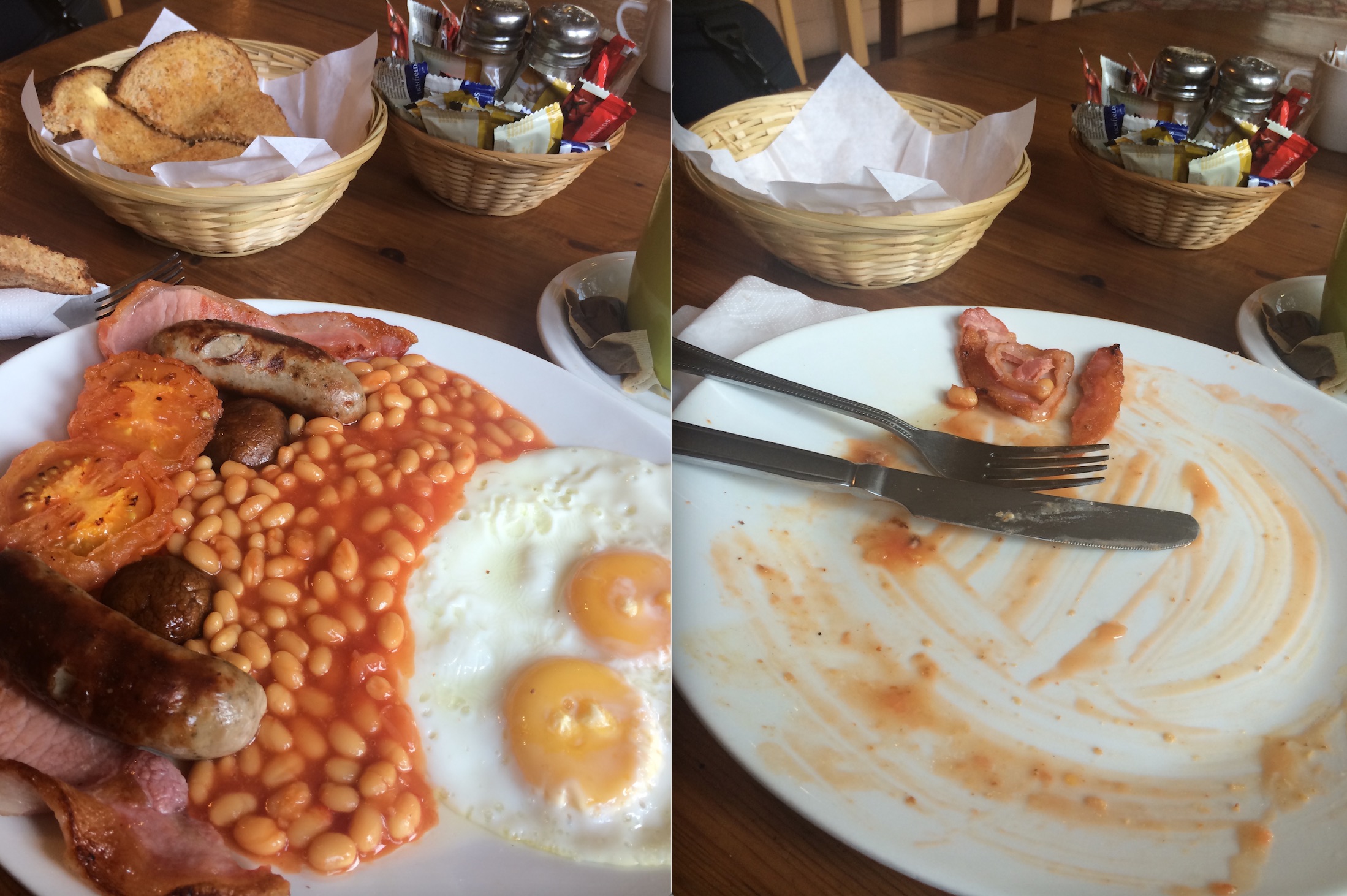

For example, millions of us open our phones every few minutes and become absorbed in a technoculture that we don’t understand. This weekend I did something I swore I would never do.

I texted a picture of my breakfast.

Oh no, I thought. I’ve become one of those narcissistic sharers I used to make fun of. I’m a wannabe Millennial!

But there’s more to this than meets the eye. For starters, you need the right tool for the job.

Picking the smartest tool in the shed

Selecting tools requires critical thinking: What IS the job? What do we want to accomplish by sharing information? And what tool to use? How does a tablet compare with a composition book? Is it best to use an online format that supports text? Photos? Video? Music? Interaction/ conversation?

What are we trying to say, and what impact do we want to make on the person or people to whom we say it?

We no longer tell the stories of our pictures. Our pictures tell the stories of us.

It’s not a tool, it’s a way of life

I didn’t really understand the Internet until I learned about its history and its culture from some of the people who were there when it was invented and who chronicled its influence. In particular, I am extremely grateful to Howard Rheingold for taking me under his wing and sharing so much insight with me over the years.

I have come to understand that the Internet, the World Wide Web, and the devices through which we connect are not toys, or even tools. This is not just the next evolutionary step in communication from papyrus or the printing press —this is a liminal shift that represents a new belief system and a new set of agreements, norms, attitudes, values, and rituals about how we interact and communicate.

If that sounds like a mouthful, it’s because the popular, loud, splashy, algorithmically advertised story we see in the media focuses on developing and celebrating tools. We have a great opportunity – a responsibility, really – to be more mindful about what we’re doing with these tools and how we can use them more effectively.

(Quick aside from my inner English teacher: the word technology comes from the Greek techne, which denoted, “systematic treatment of an art, craft, or technique.” [Source: Online Etymology Dictionary]. It is important to remember that technology is our artful USE of tools — not the tools themselves.)

The ‘social’ in social media

I gave all of this some* (*like part of a second’s worth) thought before I whipped out my iPhone and started snapping pics of my breakfast.

My reason was important to me. I missed someone and I wanted to share the meal with her.

I didn’t care if anyone else on Earth knew what I had for breakfast. (I’m a very private person, but since I’ve told you this much, it was a chicken and bruschetta omelette with melted cheddar cheese on top — and it was UH-mazing.)

The only reason I was moved to curate anything at all was because I wanted to share the experience with the person I cared about most. I didn’t want to post on Twitter, or Facebook, or Instagram, or any other potentially “public broadcast” space online. I just wanted to send a personal breakfast message to one person.

Even before the pandemic began, we have more reason now than ever to communicate online. Children who live in two homes reach out and share with their parents. Relatives who move stay in touch long distance. Young people find ways to connect since they don’t have the same opportunities that today’s adults once did to meet, play, collaborate, and resolve conflict in unsupervised physical space.

Change the channel

We also have more reason than ever to carefully consider the online channels we use to communicate. In Marshall McCluhan classic words, “The medium is the message.” It’s fascinating to see how even familiar media create different understandings when we use them in different contexts.

It’s easy to see that turning in an essay on paper is different than using an electronic format, but it’s also important to recognize that the same electronic artifact is seen differently when it’s presented on Facebook, or a blog, or a 1.0-style website, or Pinterest, or… (pick your favorite sharing media platform).

Get the picture?

Consider a familiar artifact: the photograph. Pictures aren’t the same now as when I was a kid, any more than a song on Pandora or Spotify is “the same” as “the same song” on a vinyl album.

When I was a kid, a 24-exposure roll of film was a scarce, expensive, valuable commodity. You took one picture at each event and you hoped your mom didn’t catch you when you burned the last couple exposures because you just couldn’t wait anymore (maybe that was just me). Then, you broke your piggy bank and went to Thrifty’s photo counter to pay $7 or so to get the film developed.

Once you got the magic envelope back with the pictures and the negatives, you’d begin the storytelling ritual. of Friends and relatives would gather round to try and recall what you were looking at. “Was that Thanksgiving?” “No, New Year’s… remember? Look: it was at Grandma’s. I didn’t have that sweater yet at Thanksgiving.”

The act of telling the stories of our pictures was a way to re/connect with the people we cared about and strengthen our memories of shared experiences.

Every time my elderly nextdoor neighbors returned from a trip, my family would be treated to dinner at their house and a slide show over dessert. Sharing images wasn’t about flashy new tools; it was the stuff of relationships and nostalgia.

Pictures are still pictures, but today our orientation to pictures and the way we experience and use them is different. Film is obsolete. Images are no longer a scarce resource. We snap 100 shots in a burst and post bunches to a variety of social media platforms.

Whether someone knows us well or only just met us, they can see what we do, what we like, where we go, and yes, what we eat. Our pictures create impressions; others who view our lives online come to “know” our identities through our photo streams.

We no longer tell the stories of our pictures. Our pictures tell the stories of us.

Process over results

So, back to my breakfast.

She didn’t get my pictures. Her iPad battery ran down again. Sometimes she forgets to charge it.

That’s OK. When it comes to building relationships, in-person communication beats all of this stuff any day of the week. Online and electronic tools can help us amplify and accelerate our thinking, but you can’t 3D print a hug. The next day my daughter came home. It was Sunday. Pancake day. She was fired up.

As we think about how to co-create and and share more dynamic learning stories, we should consider:

- Our goals

- Our audience

- The best tools for the job.

We should also have a secret ingredient. As my daughter will tell you, the secret ingredient to making good pancakes (and everything else) is Love.

Approaching our work with passion — and each other with compassion — is a great place to start. One way we can do this is by making intentional choices about how we communicate with each other.

Ars longa, vita brevis.

Thanks for reading.

(Published previously on Medium)

UPDATE: Check out this response from a high school student: