This week I’m dipping into the archives. When I taught, I took time with each new class to discuss the power of asking questions, so that learners could identify their own Big Question and launch an original interdisciplinary exploration. The following post was originally published at Dr. Preston’s English Literature & Composition 2013-2014. The original is still there, and it’s worth a click to read the students’ Big Questions in the comments. Enjoy. And please feel free to Contact Me with questions of your own. -dp

The single most powerful motivator for learning is an open question. What’s yours?

Traditional models of schooling are based on top-down instruction. The teacher delivers single-subject curriculum that is organized into component parts such as chapters, units, and lessons. Students respond via assignments, quizzes, tests, essays, and projects.

Open-Source Learning invites us to create meaningful experiences WITH people instead of FOR them. We all begin our lives insatiably curious about the world around us, so what can we do to reawaken that sense of delight in wondering? For years I began the conversation with students by re-imagining the power of the question and asking them to consider one of their own. And even though I originally wrote the post below for high school seniors, you don’t have to be a student to have a Big Question; some of my favorites come from adults in leadership positions who give themselves permission to pause and wonder out loud about something they’ve always wanted to know. So, wherever you are in life:

WHAT’S YOUR BIG QUESTION?

Our minds are naturally inclined toward associative and interdisciplinary thinking. We connect the dots in all sorts of ways, often when we don’t fully comprehend the experience (and sometimes even when there aren’t any dots).

We have questions about the nature of the world: our experience of it, our place in it, our relationship to it, what lies beyond it… When we’re young we ask questions all the time. We are insatiably curious. It’s like somehow we intuitively understand that the more we learn the better we get at everything – especially learning.

You’re a natural

No one is born with test anxiety. When we’re young, we test and challenge ourselves all the time. As we age, we learn to assess risk and we make better decisions. It’s important to keep our edge. Often the factor that distinguishes successful people is their willingness to risk and fail. It’s always somebody else who’s saying, “Hey, come down from there, you’re going to get hurt!”* [*Often, they’re right. In any case they’re probably more experienced in estimating the odds of that was fun didn’t hurt vs. itchy leg cast for a month outcomes. But sometimes you just KNOW you can do it and it’s frustrating to be told you can’t. Pushing the edge is what learning is all about.** {**As a teacher/responsible adult I must explicitly remind you to do this (i.e., learn/push the edge/create new neural pathways in your brain that actually change your mind) in ways that will not break laws or harm any sentient beings– most especially you– or offend, irritate, annoy, upset, or anger your loved ones.***} <***If you think this is a lot of footnotes, or whatever we’re calling the blogger’s equivalent, you should read David Foster Wallace (especially Infinite Jest). In fact, this is a good time for you to consider his commencement speech (which doesn’t contain footnotes, but does contain the sort of wisdom that more people should attend to while there’s still time to do something about it.> At any rate, if you’re still following this sentence you’ll do fine in this course.>}] Not only do we love climbing learning limbs when we’re young, we know it’s what we’re best at. Many of us learn whole languages best between the ages of 5-12. [Or earlier.] Our amazing brains manage the torrential inflow by creating schema.

You have been trained in captivity

We need to accelerate and amplify our learning. Our future is complex and uncertain. Those in the know will thrive. Learning helps our brains develop. In fact, scientists are investigating whether the lack of new neuron formation is a cause for depression or an interfering factor in recovery.

Learning is trapped in school. By definition, individualism and divergent thinking don’t regress to the mean or conform to a one-size-fits-all syllabus. Even the smartest and most successful learners fear punishment or embarrassment, so they surrender and play the game.

Learning that starves for opportunity dies the same death as a fire that starves for oxygen.

The authors of “The Creativity Crisis” say we ask about 100 questions a day as preschoolers– and we quit asking altogether by middle school.

In his (wonderful!) book Orbiting the Giant Hairball, Gordon MacKenzie describes visiting schools to show students how artists sculpt steel into animals:

“I always began with the same introduction: ‘Hi My name is Gordon MacKenzie and, among other things, I am an artist… How many of you are artists?’

The pattern of responses never failed.

First grade: En mass the children leapt from their chairs, arms waving wildly, eager hands trying to reach the ceiling. Every child was an artist.

Second grade: About half the kids raised their hands, shoulder high, no higher. The raised hands were still.

Third grade: At best, 10 kids out of 30 would raise a hand. Tentatively. Self-consciously.

And so on up through the grades. The higher the grade, the fewer children raised their hands. By the time I reached sixth grade, no more than one or two did so and then only ever-so-slightly—guardedly—their eyes dancing from side to side uneasily, betraying a fear of being identified by the group as a ‘closet artist.’”

You have the key

Richard Saul Werman (the man who created the TED conference) said, “In school we’re rewarded for having the answer, not for asking a good question.” School and the way it works was designed back when things were very different and oriented around mass production; that’s not the way the world works any more. Learning should be more than preparation for a job that may not even be around by the time you graduate. And in the age of the search engine, there is no real point in learning facts for their own sake, especially since so many of them eventually turn out not to be facts after all.

You have to develop the critical thinking and collaborative skills that will enable you to identify opportunities, solve problems, and CREATE a role for yourself in the new economy. (And don’t worry – if you’re not interested in being an entrepreneur, these abilities will help you do whatever else you want to do more effectively.)

When we’re young we ask questions all the time. We are insatiably curious. It’s like somehow we intuitively understand that the more we learn the better we get at everything–including learning.

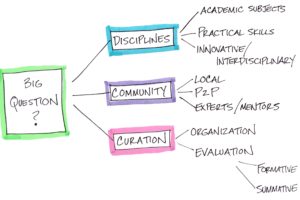

So, our first mission is to reclaim the power of the question. Everything you ask has an interdisciplinary answer. Show me a cup of tea and I’ll show you botany, ceramics, and the history of colonialism (for starters). Wondering why your girlfriend doesn’t love you any more? Psychology, poetry, probability… you get the idea. And no matter what the question or the answers, you’re going to have to sort the signal from the noise and determine how best to share the sense you make.

What’s your Big Question?

I have some questions for you. What:

- have you always wanted to know?

- are you thinking about now?

- information would make a difference in your life, or in the community, or in the world?

- do you wish you could invent?

- problem do you want to solve?

This is not a trick and there are no limits. Please comment to this post with your question and post it to your course blog (title: MY BIG QUESTION). You can always change your question or ask another. If you need some inspiration, check out this year’s Eng 3 Big Questions here.

[Originally published at Dr. Preston’s English Literature & Composition 2013-2014. It’s worth a click to read the students’ Big Questions in the comments.]