Month: September 2022

-

a tale of two teachers

This is a description of last week in the life of two teachers. The second teacher is the one to remember. The first teacher is me Last week I accepted Ash Kaluarachchi‘s kind annual invitation to serve as a “shark” for startup founders at EdTech Week in New York City. It’s always great to see…

-

we belong

The clerk at the 7-11 on Pacific Coast Highway smiled as I brought the coffee to the counter. “Where are you going at three o’ clock in the morning?” To my very first triathlon. I signed up for the Malibu Triathlon (1.5k ocean swim, 40k bike ride, and 10k run) as my first training event…

-

madeleine moment

An average guy is having an average — no, make it a mediocre, even crappy day. He comes home and his mother gives him a little cake and tea. The experience blows his mind. In his words: “One day in winter, as I came home, my mother, seeing that I was cold, offered me some…

-

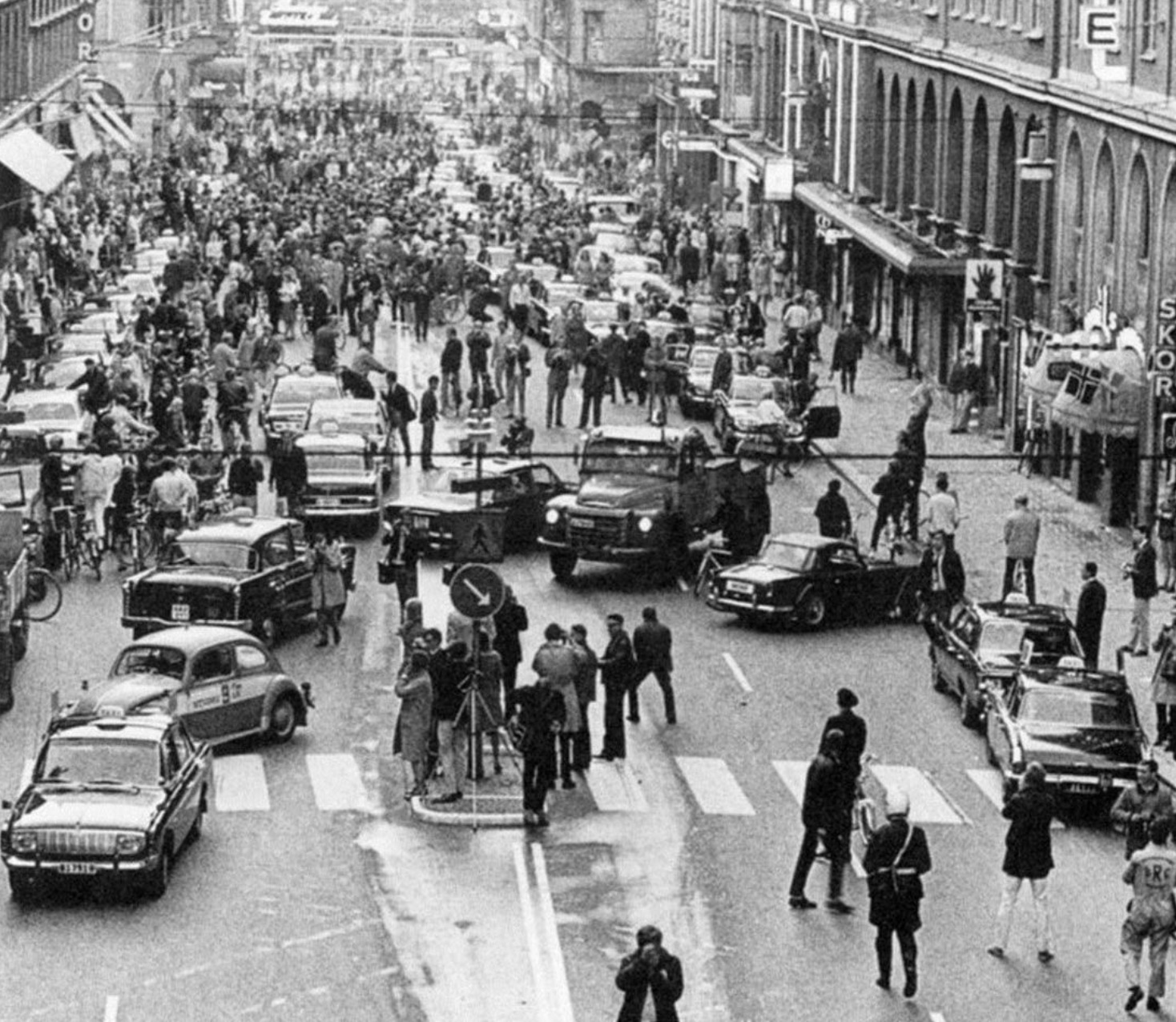

make change

Open-Source Learning represents a significant change in education. Gone are the syllabi. Gone are the textbooks. Gone are the days when teachers had to act like all-knowing content experts and sergeants-at-arms. Heraclitus, I believe, says that all things pass and nothing stays, and comparing existing things to the flow of a river, he says you…