Month: December 2022

-

new year’s resolution to finish what I star

I constantly look for new beginnings. Every culture has rituals and traditions for ending and beginning chapters, and I celebrate them all. But we don’t really need a calendar reminder to be our better selves. Today* (*whatever day you’re reading this) is the perfect opportunity to reinvent yourself. Do that thing or practice that quality…

-

writing is dead long live writting

Over the last few days I received notes from friends and colleagues expressing concern that ChatGPT will be the end of writing. These are intelligent, caring people. I can’t imagine any of them ever outsourcing their expressions of thoughts and feelings to an AI Chat Bot. Each considered the issues and wrote to start a…

-

do or do not do. there is no essay.

Before the pandemic I asked 150 high school juniors in four separate classes to think of a word they associate with writing essays. After giving them a couple minutes to think, I stood at the board and wrote down the words they called out. Here are the lists: As you can see, the students’ feelings about writing…

-

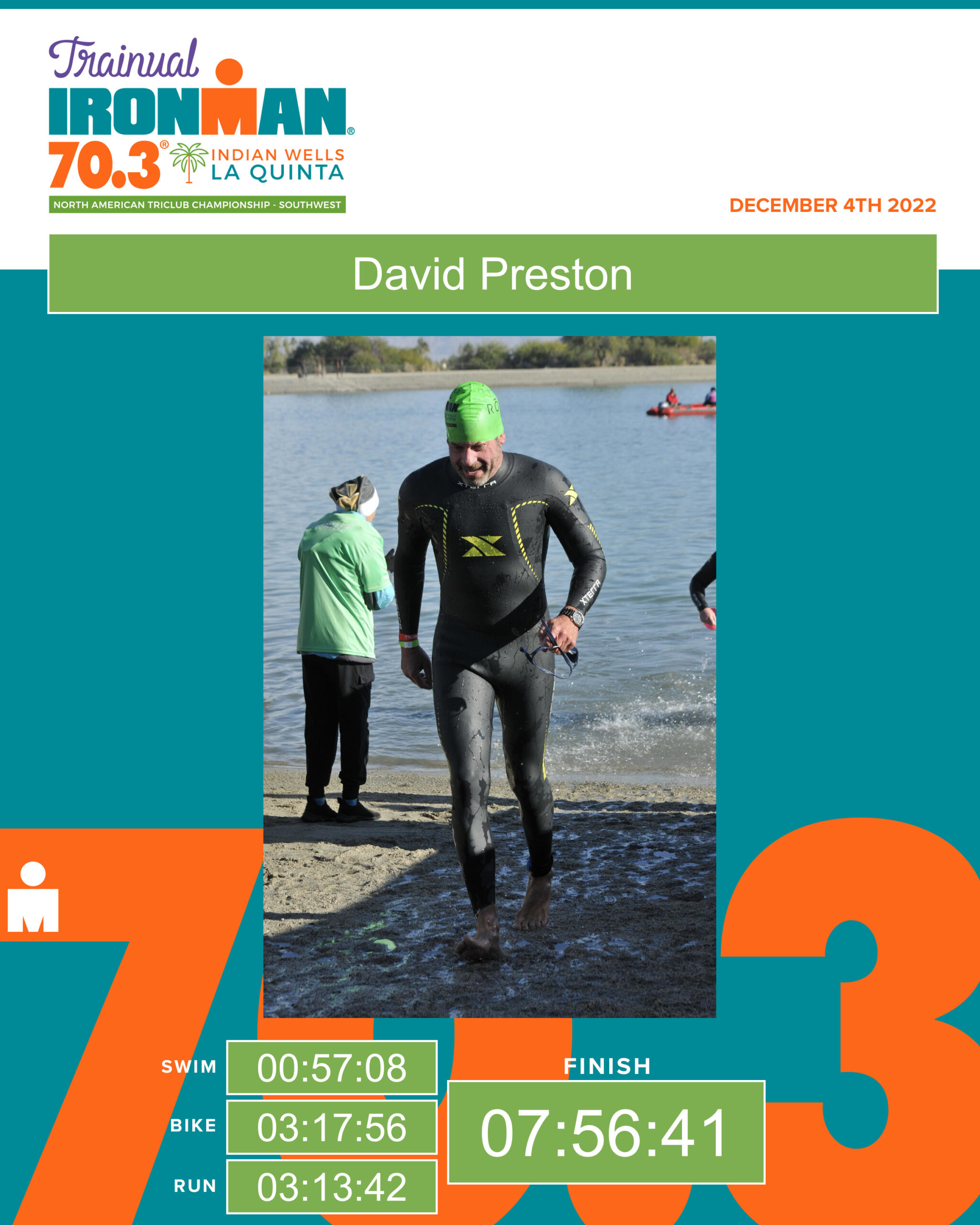

The OSL Making of an Ironman

The meaning of life is to give life meaning. Viktor Frankl Everything I do means something to me. At 3:45 on Sunday morning I pulled into the parking lot of the Indian Wells Tennis Gardens and did something I’d never done before. I wrote a prayer. I wasn’t asking for anything, I just had a…