Month: January 2022

-

webinar guest: chris carfi

Last fall, my good friend Chris Carfi came up with a terrific idea. “David,” he said, “I have a Web3 idea that I’d like to turn into an Open-Source Learning journey.” Over the next few months, Chris did a deep dive into: NFTs DAOs Ways in which Web3 might be able to transcend the “rich-get-richer”…

-

You can’t win if you don’t learn to read

Re/Connecting People, the Written Word, and the Delight of Discovery. Everyone must learn to read. You can’t get anywhere in this world if you can’t read. Whatever else you do in life, you will have to navigate a world of contracts, warranties, and user agreements. Reading is essential to surviving and thriving in today’s world.…

-

What’s your big question?

This week I’m dipping into the archives. When I taught, I took time with each new class to discuss the power of asking questions, so that learners could identify their own Big Question and launch an original interdisciplinary exploration. The following post was originally published at Dr. Preston’s English Literature & Composition 2013-2014. The original…

-

Making the cut

“You Don’t Get It” The single biggest problem in America today is our lack of understanding. We are not going to solve the environment, the economy, the government, or anything else unless we can comprehend, communicate, analyze, evaluate, and act on big ideas. A lot of ink has been spilled about empathy – there’s even…

-

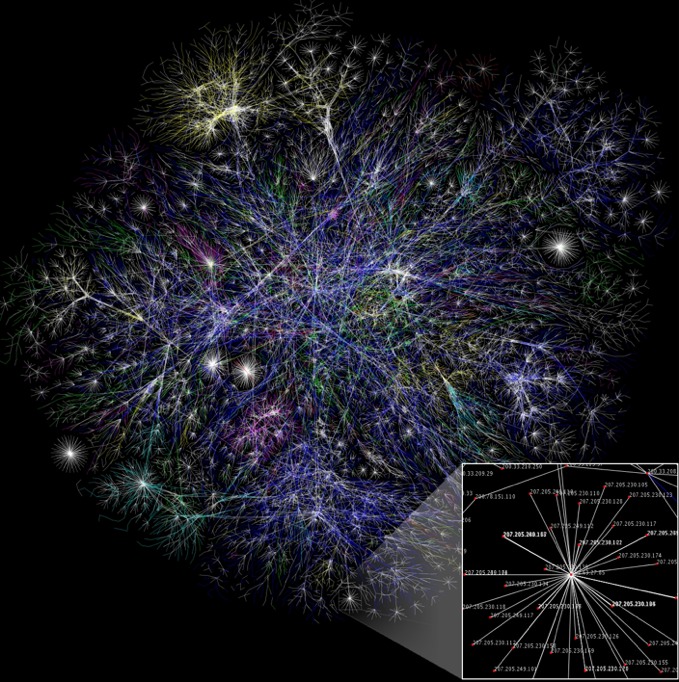

Learning on web3

Happy New Year! 2022 promises to be a(nother) dynamic year in education. Our environment, our culture, and the coronavirus continue to evolve, and we must adapt. Open-Source Learning is based on systemic interaction between us as individuals, our immediate network, and our surroundings – what is happening out there that may enrich our experience? Learners…