Month: November 2021

-

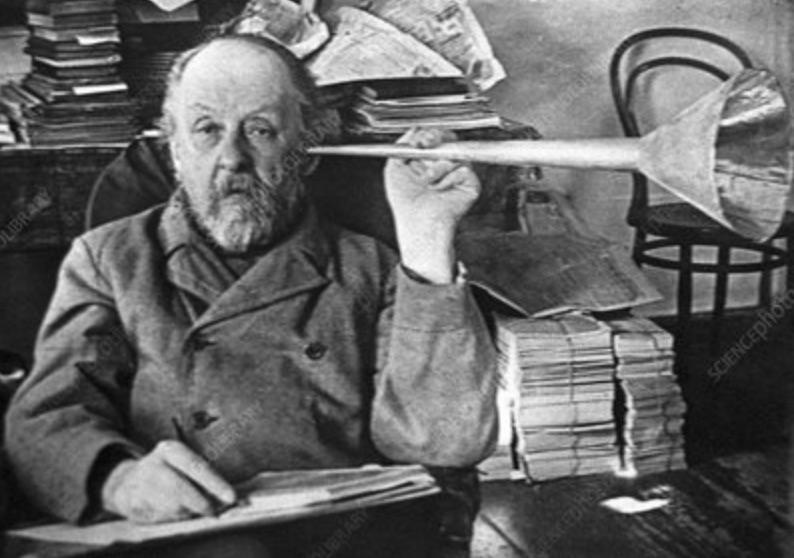

How’s that sound?

Previously, I wrote about how terroir affects our learning and what we can do to improve the physical design of our learning spaces. In those posts I considered our visual and tactile experience of learning spaces. What about acoustic design? Learning is challenging enough when you can hear what’s being said. But when the course…

-

Re(des)ign of terroir (part two): 7 ways to hack your headspace

You would think that school spaces would be designed to optimize learning. You would be wrong. School spaces are most often lessons in how not to design for learning. I once taught a course on organizational team building for grad students in the Anderson School of Management at UCLA. We were scheduled in an austere…

-

Reign of terroir (part one)

There are green chiles, and then there are Hatch, New Mexico green chiles. There are tomatoes, there are Roma tomatoes, there are San Marzano tomatoes, and then there are the Pomodoro San Marzano dell’Agro Sarnese-Nocerino from the Sarno Valley. If you cannot tell the difference, you are not allowed to make a Vera Pizza Napolitana.…

-

A few bad apples

The classroom conversation took place in 2014 but I remember it like it was yesterday: “OMG Dr. Preston that’s so cliché…” Huh? I looked up from my desk to see one of my most successful seniors – who gained admission to Princeton, University of Michigan, UCSD, and UCSB, and earned a full ride at Ohio…

-

EdTech of the dead

Every reference I can find for the etymology of the word technology has to do with, “art, skill, or craft.” Technique comes from the same root. Any system of making or doing requires qualities such as dedication, skill, and patience. Technique/technology may or may not involve tools. But whenever I hear people talk about education…