Month: October 2021

-

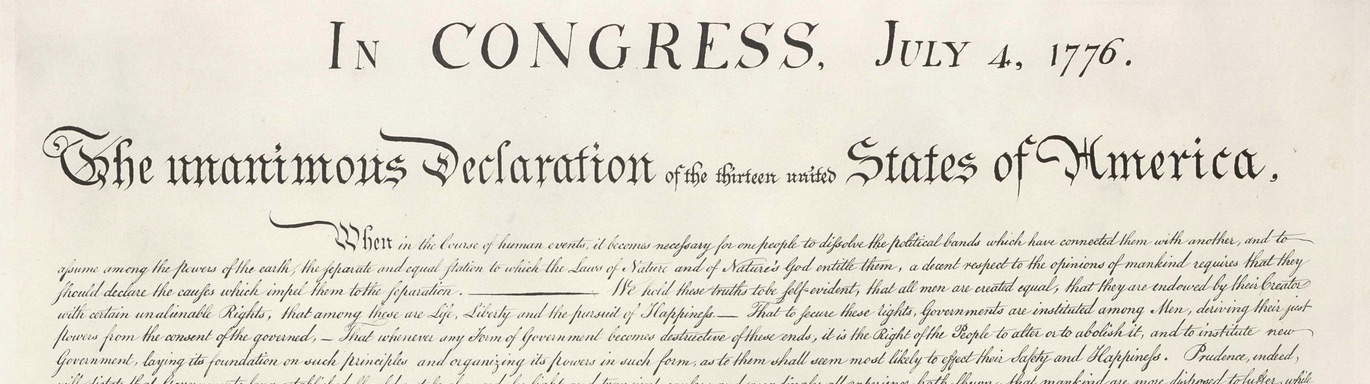

Declare your digital interdependence (O…SLAP!)

Going online these days is like walking through a trade show in an office building full of corporate lobbies. While you’re trying to decide where to do your business – Google, Microsoft, Apple, Amazon – banner ads and pop ups constantly compete for your attention. You can’t read two paragraphs before something blocks your view…

-

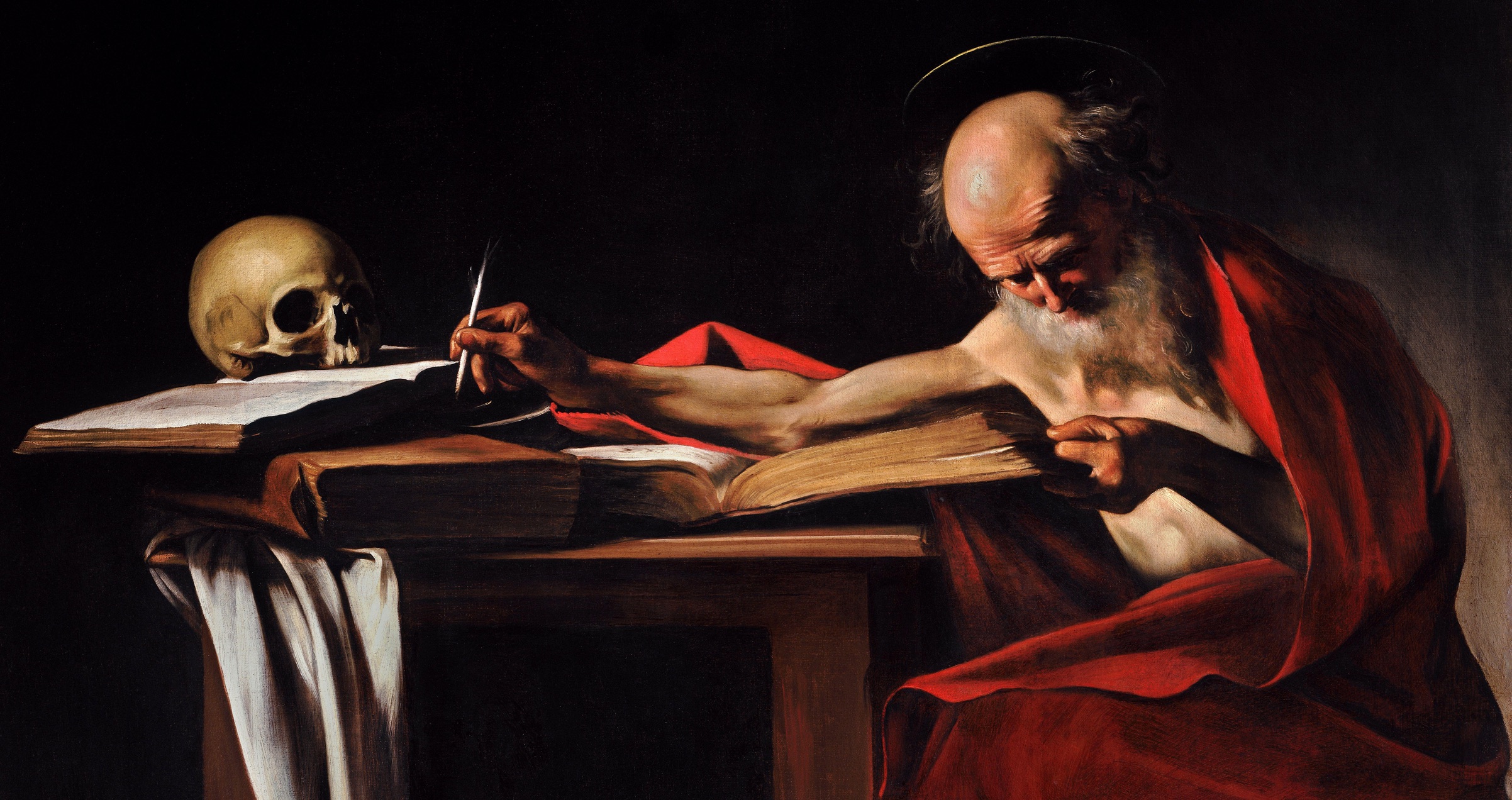

A language lesson from the dead

Headline-Induced Whiplash Last week this headline hijacked my attention: “Southlake school leader tells teachers to balance Holocaust books with ‘opposing’ views.” What? No. HELL, NO. Apart from the stunning ignorance, and the moral and ethical problems with the statement, the fact that this mandate came from a school district director of curriculum – who was…

-

Turn into the skid

On a rainy winter night in 1987, when I was a senior in high school, I drove my parents’ Oldsmobile sedan “over the hill” from the San Fernando Valley to visit my girlfriend at her UCLA dorm room. On my way home I totaled the family car. More on that in a few paragraphs. There…

-

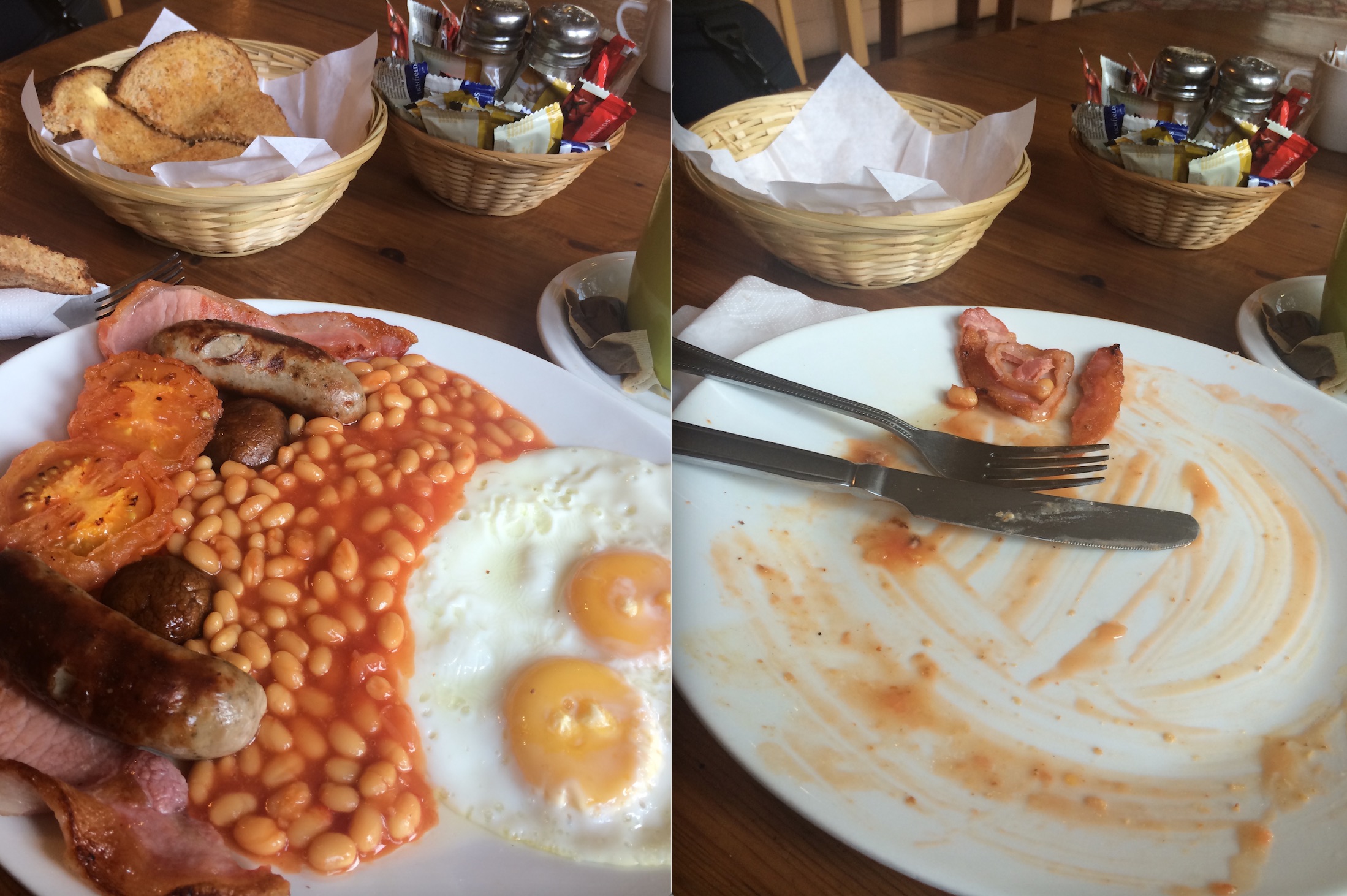

We eat social media for breakfast

How we engage with social media continues to increase influence our economy, our social and political culture, and our personal lives. Open-Source Learning invites us to consider and reconsider how we engage with our devices, platforms, and software. Self-awareness has become more important than ever. An entire generation is growing up on the screen.…